One of the benefits of having a (very) wide range of interests is that every so often a flash of insight gets dropped into my lap. In this case, it was a matter of “We must recognise that single events have multiple causes” showing up as a suggested read from Aeon on the same day that Thomas Power retweeted this:

The image in the tweet is an excerpt from an interview with Rory Stewart, Conservative Member of Parliament for Penrith in the UK. The collision of themes between the two articles struck me.

“You get there and you pull the lever, and nothing happens.”

The behavior of a system is determined not by the structure of the components of that system, but by the relationships and interactions between those components. Moreover, those relationships and interactions are dynamic and complex, even when that’s contrary to the designer’s intent. In fact, the gap between the behavior as intended and as experienced introduces a tension. I would argue that it’s less a matter of nothing happening when the “lever” is pulled and more that something different from what’s expected happens. Rather than simple cause and effect, “if this, then that”, multiple factors are in play.

In mechanical systems, parts wear, subtly changing the physics of the mechanism. Foreign objects invading the system can impose change in a more dramatic fashion. Context, both that of the system’s internals and its environment, influences its operation.

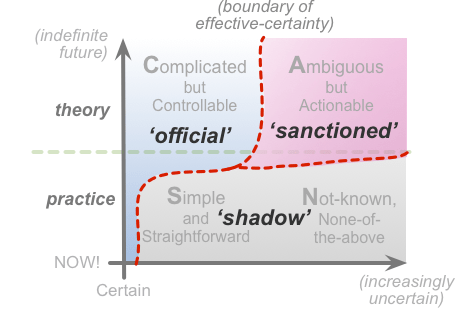

As was noted in the Aeon article, agency adds to the complexity. In social systems, all of the “components” are individuals with agency, making those systems chaotic in at least the colloquial sense of the word. Using Tom Graves’ sense-making framework, SCAN, these interactions fall into the more uncertain quadrants, either “Ambiguous but Actionable” or “Not-known, None-of-the-above”. Attempting to deal with them as though they fell into the “Simple and Straightforward” quadrant increases the likelihood of getting unexpected results.

Learning/sense-making is critical to dealing with change, whether internal or external (or both). The manner in which change is appreciated and reacted to, affects the health of the system. Consider three boilers: one where pressure is continuously monitored and adjusted, one which is equipped with a pressure relief valve which will open prior to a catastrophic failure, and one where problems are signaled by an explosion. It’s a trivial exercise to come up with examples of social systems, from businesses all the way up to political systems, using the third method. It’s probably a more interesting exercise to consider why that’s the case for so many.

In a recent post, “Architecting the shadows”, Tom Graves discussed the phenomenon of ad hoc, unofficial “shadow” organizational interactions that arise in order to get work done:

In SCAN terms, we could summarise the generic positioning of all ‘shadow’ functions – shadow-IT, shadow-business-models, shadow-management and more – much as follows:

In other words, the ‘shadow’-world exists to deal with and resolve all the uncertainties and over-simplifications that overly-mechanistic management models tend to overlook. Even in more aware management-models, in which some exploration of the uncertain is officially sanctioned and allowed, the shadow-world will still always need to exist – particularly whenever the work gets closer towards real-time action:

In closing the post, Tom makes the following observation:

As the literal ‘the architecture of the enterprise’, a real enterprise-architecture must, by definition, cover every aspect of the enterprise – including all of the ‘shadow’-elements. And yet, also by definition, those ‘shadow’-elements cannot be brought ‘under control’ – not least because they deal with the themes and factors that are beyond the reach of conventional concepts of ‘control’.

The “conventional concepts of ‘control'”, the deluded belief that complex interactions can be managed as though they were simple, poses an immense risks to organizations. Even attempting to treat those interactions as merely complicated, rather than complex, introduces a gap between reality and perception, between “the way we do things” and the way things actually get done. When the concept and reality of the system’s interactions differ, it’s more likely that the components of the system will wind up working at cross-purposes.

In a comment on Tom’s post, I noted that where the shadow elements are a “French Resistance”, flouting the rules in order to actually get work done, that’s a red flag.

The most important thing to learn about management and governance is knowing when and how to manage or govern and more importantly, when not to. Knowing what can actually be controlled is an important first step.

The approach to single event with multiple causes can be addressed with Dean Gano’s “Apollo Method: Root Cause Analysis” and the tool Reality Charting

LikeLiked by 1 person

Terrific post, as usual. I completely agree with your conclusion. Having worked directly with “shadow” teams that operated in the wide open, I have seen the enormous inefficiencies that can be allowed to grow when management and governance goes awry. The best companies I know start with a simple premise: control the controllables. Good things tend to follow.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Matt…very much appreciated.

LikeLike

Pingback: SPaMCAST 411 – Servant Leadership, Systems Thinking, Craftsmanship, Requirements | Software Process and Measurement

Pingback: Form Follows Function on SPaMCast 411 | Form Follows Function